Dolphins DT Durval Queiroz, who lived on a farm in Brazil, working on different field in NFL

DAVIE, Fla. — Once a week for roughly a year, Dolphins defensive tackle Durval Queiroz Neto would drive three and a half hours to football practice. He’d head south from the family cattle farm in his hometown of Diamantino in central Brazil down to Cuiabá. He’d bang heads with his teammates for a couple of hours – practices were always full contact, tackling to the ground – and then drive back home. Game day travel could be worse, much worse. If his team was playing in Sao Paulo, Queiroz would drive to Cuiabá and then take the 24-hour bus ride with the rest of his team to the game. If they were playing at Santa Catarina, it was a 30-hour bus ride.

“I don’t think there’s any team in the country that flies all their athletes to the game,” said Kenneth Joshen, Queiroz’s coach in Brazil and his agent in the NFL.

Whatever the sacrifice, the 26-year-old Queiroz, a nationally ranked judo player in the soccer-crazed nation of Brazil, thought it was worth it to continue playing American football, a sport he first tried on a whim in 2015.

Joshen, who played college football at Coastal Carolina and later played in the Arena league for the Cincinnati Commandos and Northern Kentucky River Monsters, thought so, too.

Joshen, who started coaching in Brazil in 2011, knew he had something special in Queiroz, a raw but athletic 6-foot-4, 325-pound gem who was agile enough to do a backflip. Joshen had never seen a Brazilian so good at American football.

Joshen’s goal quickly became getting Queiroz into the NFL International Player Pathway, a three-year-old discovery and development program that offers athletes from other nations a shot at playing in the NFL.

The strategy worked. Queiroz was signed by the Dolphins in April.

“This is a big dream, man,” he said. “I can’t imagine how many people want to be in my place right now.”

Queiroz has three ways to stick with the Dolphins through the regular season. He could be added to the practice squad with a special 11th man exemption. He’d be ineligible for promotion to the 53-man roster but he couldn’t be cut. He could practice and he could travel to every game with the team. It’d be roughly the equivalent of a redshirt season in college.

Another option would be adding Queiroz to the regular practice squad. He’d be eligible for promotion to the 53-man roster and would be eligible to be poached by any other team off Miami’s practice squad. But he could also be cut.

The third option is making the 53-man roster out of training camp, which would mean he’s just like any other NFL player, free to be traded, cut or sent down to the practice squad.

The first option seems the most likely.

“We’re projecting him as a two-year, down-the-road guy,” said Will Bryce, head of football development for NFL international.

Somewhat predictably, Queiroz’s journey to the NFL wasn’t easy.

There were extreme highs, frustrating lows and the mandate from Queiroz’s parents that he finish his degree in agronomy, the science of soil and plants, before traveling to the United States.

“When faced with the possibility that Durval went to the United States to try to fulfill his dream of playing in the NFL,” Patricia and Eugenio Queiroz said via email, “we, as parents, conditioned that he should finish the college of agronomy first and that this would be a security for his life, and that if nothing happened in the United States, he would return to Brazil and could practice agronomy at the family farm or anywhere else he wanted to go.”

Joshen did his part to keep the dream alive.

“I think I called the league office every day for like two months trying to contact somebody,” he said.

He sent video and measurables of Queiroz to every team as well as a host of general managers, coaches and scouts.

“That ended up getting passed across to my desk,” Bryce said.

Around March 2018, Bryce informed Joshen he wanted to see Queiroz, who was now in the United States working out at TNT Sports in Williamston, S.C., at a private workout.

“Me and Durval, we started crying,” Joshen said. “We were happy because we knew this was his opportunity to play in the NFL.”

Queiroz crushed the workout, running a 4.9-second 40-yard dash and recording a 31-inch vertical jump.

The real highlight was his 6.9-second three-cone drill.

“That’s kind of unreal,” Joshen said.

By comparison, Notre Dame defensive tackle Jerry Tillery, the first-round pick by the Los Angeles Chargers, ran a 7.45-second three-cone drill. Mississippi State defensive end Montez Sweat, Washington’s first-round pick, ran a 7.0-second three-cone drill.

“The scouts told him to run it again,” Joshen said of Queiroz. “They didn’t believe it. Then he ran a 7.04 right back with no break.”

Bryce, who is based in London, liked what he saw and kept in touch.

In late 2018, Bryce traveled to Brazil to see Queiroz play.

“He dominated the game,” Bryce said. “He had something like three sacks in the first quarter.”

After the game, Bryce told Queiroz he’d played his last game in Brazil. He presented Queiroz a letter saying he’d been accepted into the NFL International Player Pathway.

“It was pretty intense,” Joshen said.

Queiroz attended a 12-week training program at IMG Academy in Bradenton, Fla., with the other six members in the program. That was followed by a combine in front of all 32 NFL teams on April 1 at the Tampa Bay Buccaneers’ facility.

Queiroz was signed by the Dolphins on April 8.

The magnitude of this opportunity isn’t lost on Queiroz, who is being watched by thousands of Brazilians back home. He had 5,000 Instagram followers before signing with the Dolphins. He has 50,000 followers now.

“They are proud of me because nobody could imagine I would make it,” he said. “I never played in high school or college. This proves what God can do in somebody’s life when you have a dream and you work hard.”

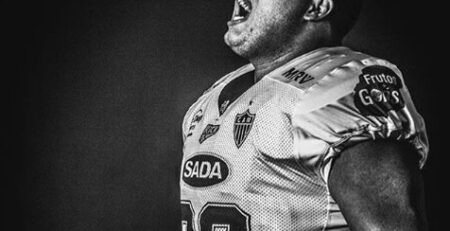

Defensive tackle Durval Queiroz Neto, of Brazil, is interviewed during voluntary minicamp at the Dolphins training facility (Lynne Sladky / Associated Press)

God-given skills

Queiroz grew up on the family farm in Diamantino (population 18,000) and it was always assumed he would eventually help run the business. Even when he went away to college he’d return home every weekend to do farm work.

“My whole life I was preparing to come back home and help my father on the farm,” he said.

Farm life is the reason Queiroz got a degree in agronomy, a branch of agriculture dealing with crop production and soil management.

“He studies the sun, the placement of the sun, all these types of things with the grass and the soil,” Joshen said.

Farm life is so important to Queiroz that when he has kids he wants them to also grow up on a farm.

“Farming I think is a better place where you can grow, where you can understand where things come from,” he said, “because sometimes we need to learn how to appreciate the great things of life like the animals, the plants and everything God gave to us.

“It’s really important. The people in the city, normally they don’t understand. They go to the store. I know how to survive. This is real important. … They can grow up on a farm until like 14 and then after they can go to the big city for a better school and stuff like that. But I want my kids to learn where the things come from. Then after they are ready for the world.”

His parents knew nothing about American football until Durval began playing.

Now they know one team, the Miami Dolphins, and one player, their son.

“We knew nothing and we still know very little,” Patricia and Eugenio Queiroz said. “We were able to define when our team’s defense is on the field and the opponent is on offense, and that when the player runs with the ball and crosses the last line of the field, it’s a touchdown. We are learning slowly.”

Queiroz was a judo standout.

“You should see the shrine of trophies he has,” Joshen said.

Queiroz started in judo at 4 years old and continued until he was 20. He played some soccer, like most Brazilians, but got too big for the sport.

One day at college a group of guys spotted Queiroz on campus, leaned out of their car and yelled to him, “Hey, you, big guy … come here!”

They explained they played American football and wanted Queiroz to give it a shot. It was nothing fancy, to be sure.

“We don’t have equipment or anything,” they explained. “It’s just hit who has the ball.”

So that’s what he did. Quickly afterward he fell in love with the sport.

“After that, I called my dad and I said I want to transfer and move to a city and I want to play on a real football team, and I did,” he said.

Queiroz, his brother and his father showed up at a Cuiabá practice one day in 2015, instantly drawing Joshen’s attention. Eventually, Queiroz practiced with Cuiabá. He was an instant sensation, not only because of his size but also because of his body control.

“The way he was moving,” Joshen said. “He’s quick on his feet. He had a real quick first step off the line. We were trying to snap the ball he was in the backfield before the quarterback got the ball.”

The more Queiroz played – he eventually transferred and attended college in Cuiabá, ending the three and a half hour drive to practice – the more dominant he became. Joshen heard about the NFL International Player Pathway and got an idea. He was already in law school studying to become certified as a NFL agent. He’d be done in 2017.

“I was like, ‘Hey, I’m going to take you with me, man,’ ” Joshen told Queiroz about the NFL. “He was kind of like, ‘I don’t have a chance. I never went to college. I never played.’

“I’m like, ‘Hey, I’m going to get you in the league. I’m going to call everybody until we get an answer. … We had always kept in contact and he always trusted me with that.”

‘Pretty damn big’

Queiroz, called “Big Bulldozer,” in Brazil, started on his road to the NFL by first getting the league’s attention, which is no easy task.

Bryce estimates he watches hundreds of videos from international players.

“You’ll look at a lot of bad film and a lot of bad players just to find one,” he said.

Bryce has two initial requirements for initial consideration – you must be dominant in your league and you must understand English.

“If you’re not absolutely destroying the man in front of you,” Bryce said, “why on earth would you think you could do anything in the NFL? Let’s be serious.”

As for speaking English, it’s been a holdup for a few international candidates but it’s a requirement.

“It’s non-negotiable,” Bryce said.

In fact, Bryce’s courtship of Queiroz began with a series of conference calls to make sure he could speak and understand English and make sure he was serious about playing in the NFL.

After Queiroz finished school, the requirement from his parents, he committed to his NFL dream. The first things they needed were video and measurables. So Joshen had a video made of a private workout. He sent it out to teams. There was no immediate response. In the meantime, Queiroz got a visa and traveled to the U.S. with Joshen to train at TNT Sports. But it had been two months since the workout and no team showed interest. It was beginning to appear the dream was a pipe dream.

“This was the hardest part,” Queiroz said.

It was also a trying time for the family. But they held firm in their son’s NFL dream.

“At no time did we lose faith,” Patricia and Eugenio Queiroz said. “We always believed that God had a great plan for the life of our son Durval, and that with great faith God would give him a chance to fulfill his dream. We believe that faith in God leads us to realize our dreams always. We just have to believe.”

Eventually, Bryce called.

Bryce paid his visit in June 2018 to watch Queiroz’s workout at TNT Sports. But Queiroz had to return to Brazil in July because his visa expired. He re-joined his team, playing games in front of crowds ranging from a few hundred to a few thousand. Eventually, he heard from Bryce again. This time he wanted to see Queiroz play in Brazil. It was after that game that Bryce offered Queiroz a spot in the International Player Pathway.

Queiroz arrived at IMG Academy in January for the 12-week training program that involved drills, video work and nutrition.

“It’s essentially a crash course and training program to prepare them for OTAs,” Bryce said.

As a bonus, Philadelphia offensive tackle Jordan Mailata, a NFL Player Pathway alum and former rugby player in Australia, worked out with this year’s program participants. Mailata was a seventh-round pick by Philadelphia in 2018 and spent the season on the 53-man roster. Mailata is one of several alums who comes back.

“These guys come back in the offseason and they give them those insights only they can give,” Bryce said.

The AFC East is the divisional beneficiary of the Player Pathway this year, with each of the four teams getting an exemption for an 11th practice squad spot for those players. Last year it was the AFC North and in 2017 it was the NFC South.

In 2018, Carolina defensive end Efe Obada, who originally signed as a free agent with Dallas in 2015 after playing just five games with the London Warriors, became the first Player Pathway participant to earn a spot on a 53-man roster when he made the Cowboys’ squad.

With the budget-minded, rebuilding Dolphins, Queiroz has a shot, albeit a long shot, at making the roster. Among the defensive tackles are presumed starters Davon Godchaux and Christian Wilkins as well as reserves Akeem Spence, Vincent Taylor, Kendrick Norton, Jamiyus Pittman, Joey Mbu and Cory Thomas.

Defensive line coach Marion Hobby likes what he has seen from Queiroz so far. He said he’s got “twitch,” meaning he moves quickly and fluidly.

“He’s got football instincts,” Hobby said, “and I’ll be real surprised if he doesn’t tackle. We just kind of can’t get in that world (until pads are permitted in training camp).

“I think him learning more verbiage … and him just not having that great background behind is probably the only thing. But I’ve been encouraged.”

So have a few Dolphins players, most of who have only made observations from afar.

“He’s a strong cat,” defensive back Bobby McCain said.

“He’s pretty damn big,” guard Jesse Davis said. “We were like, ‘Holy shit!’ ”.

“He’s very athletic,” guard Chris Reed said. “He’s learning. I don’t watch him that much but from what I’ve seen he’s improved. He’s doing a good job. He’s working his ass off.”

Center Daniel Kilgore has also been impressed.

“He’s a strong player,” he said. “He’s played a little bit of ball, you can tell that. I’ve played with some of the international guys before and I would say he’s probably more football-developed than others I’ve played with.”

Back at Dolphins OTAs, the magnitude of the road traveled and the road ahead hasn’t been lost on Queiroz. It’s measured in things big and small. Queiroz mentioned he was talking to the team equipment manager a couple of weeks earlier.

“He said, ‘Oh, we can bring like two, three different cleats for you to try,’ ” Queiroz said. “I said, ‘In Brazil, we play like two years with the same cleats and gloves.’ Everything is different. We don’t have anything like this. We have to go on a bus like 20 hours to play a game and it’s really hard.”

So you can believe Queiroz, who is being watched by thousands of Brazilians back home, isn’t taking this for granted.

“It’s a big transition,” he said, “but I will make this through and make my family and my country proud of me.”

LEAVE A COMMENT